Fractures in Children with Preexisting Bone Conditions

This chapter aims to address more specifically the fractures that develop in children with such conditions. It is important to highlight that the scope of this topic is vast, which leads us to define the topics to be discussed.

We decided not to include fractures related to infectious processes or metabolic disorders, such as rickets or osteopsatirosis, in this chapter. Instead, our focus will be on stress fractures, considering the differential diagnosis, as well as those arising from pre-existing tumoral or pseudo-tumorous bone lesions.

Stress fractures are particularly relevant due to their nature and challenges associated with diagnosis and treatment. Furthermore, fractures resulting from tumor or pseudo-tumor bone lesions require a specialized approach to ensure appropriate management and the best possible prognosis.

Therefore, in outlining this chapter, we seek to provide a comprehensive view of fractures in children with pre-existing bone conditions, highlighting the most relevant aspects for their understanding and clinical management.

Benign Bone Tumors:

Among the benign tumor lesions of childhood, which can most frequently cause fractures, we highlight osteoblastoma and chondroblastoma.

Osteoblastoma –

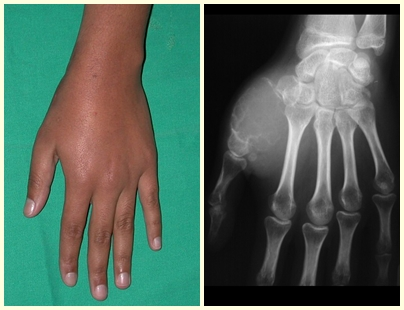

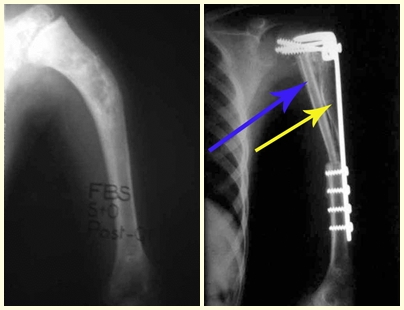

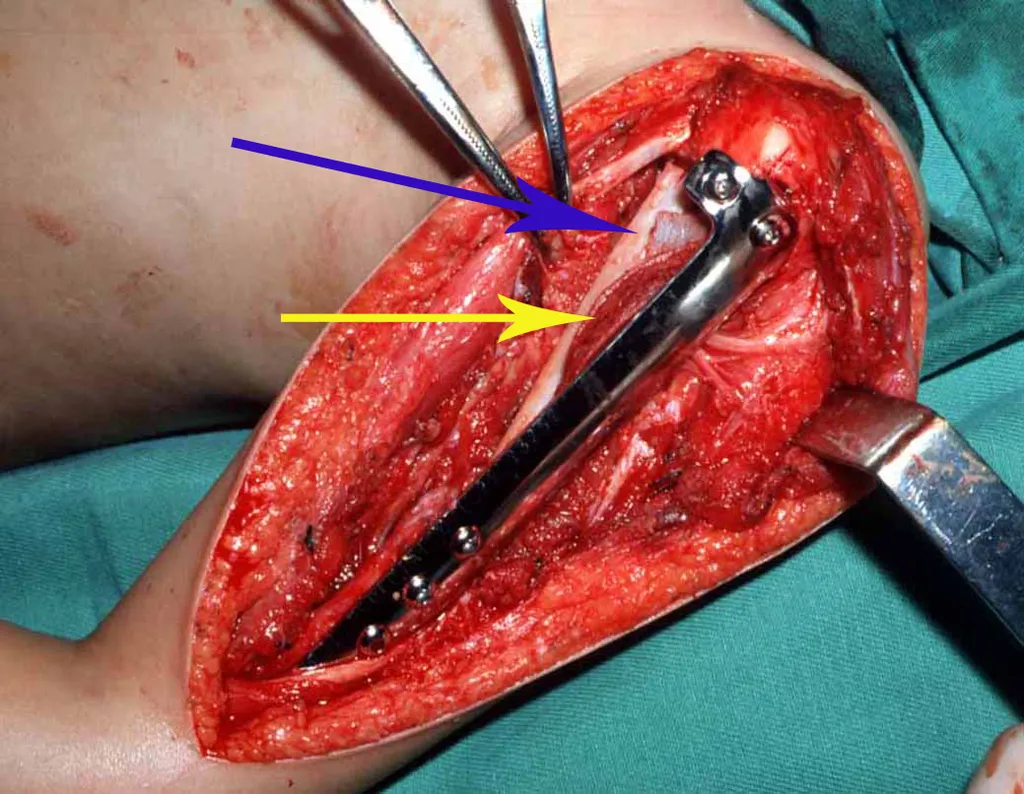

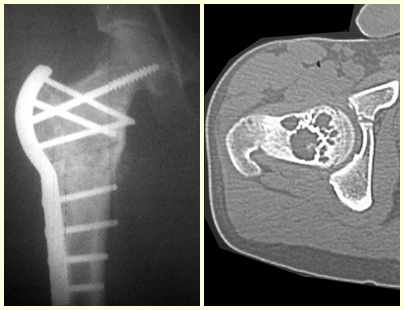

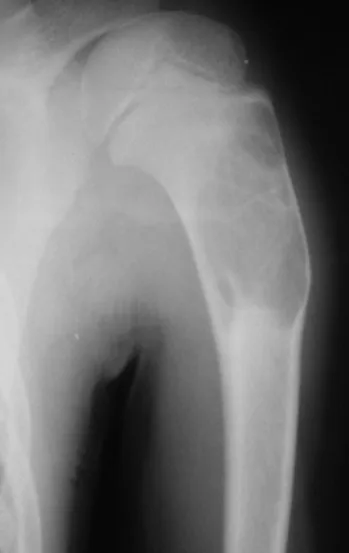

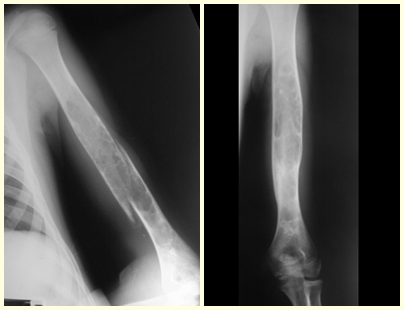

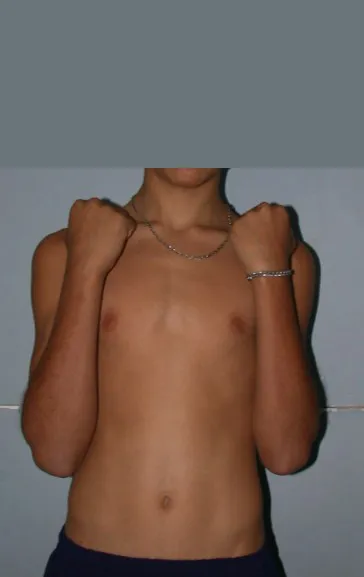

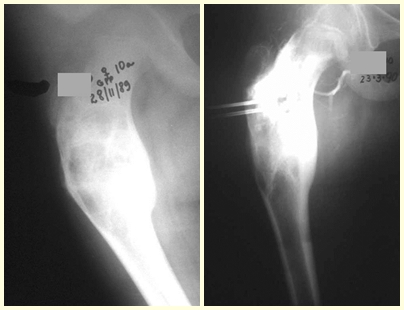

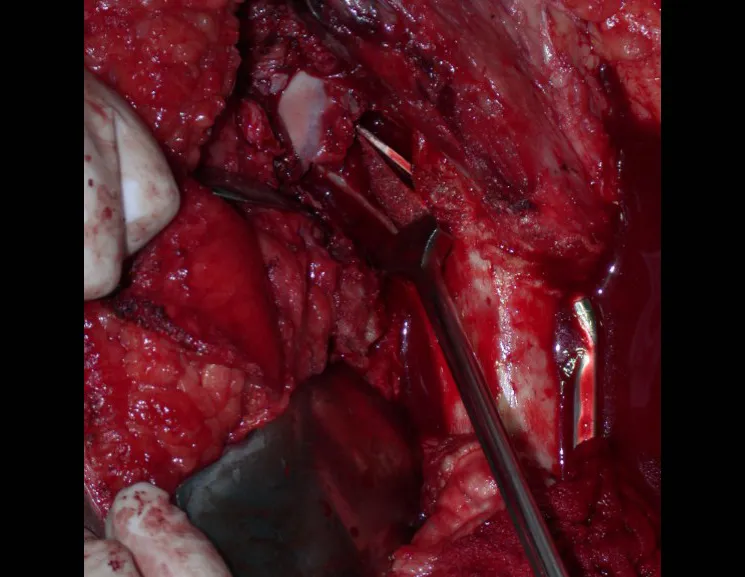

Osteoblastoma is a locally aggressive bone tumor that in long bones has a metaphyseal location, initially cortical and eccentric. This injury, as it is locally aggressive, with great destruction of the bone framework, causes micro fractures, due to erosion of the bone cortex (figs. 1 and 2). The progressive destruction of the cortex predisposes to complete fracture, when the involvement exceeds fifty percent of the bone circumference. The fracture of this lesion facilitates local dissemination, making oncological treatment difficult, which requires elaborate reconstructions and there is a limitation in functional recovery (Figs. 3 and 4).

Chondroblastoma –

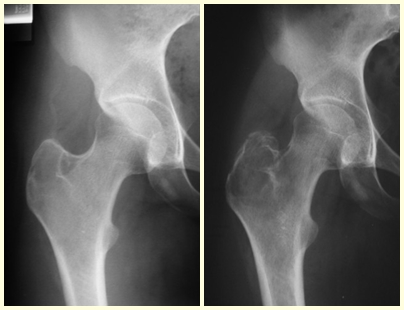

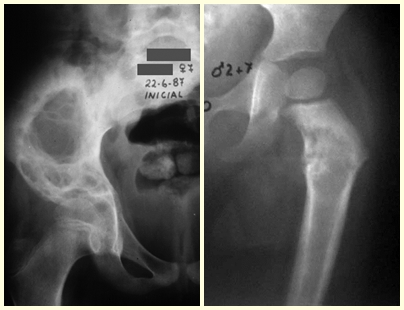

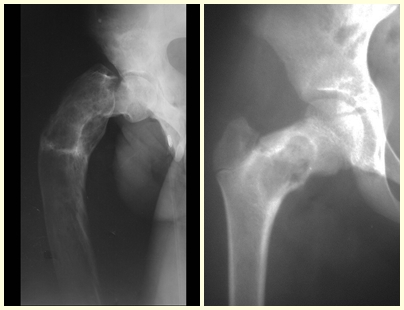

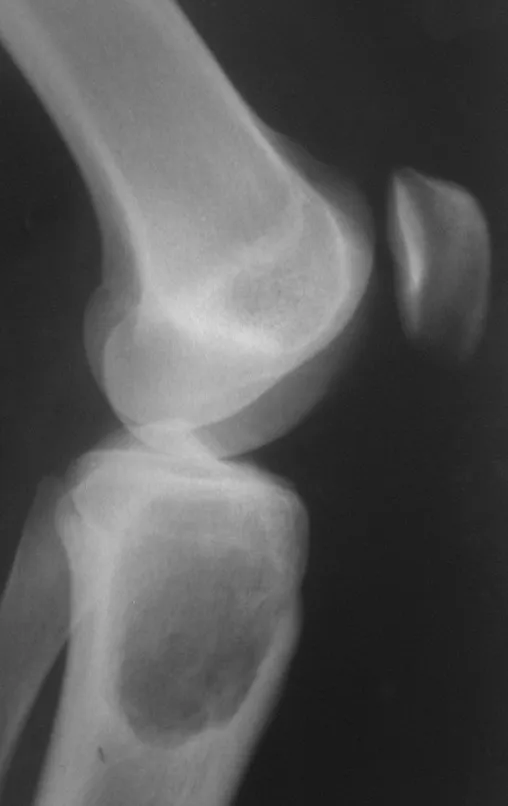

Chondroblastoma affects the epiphyseal region of growing long bones (figs. 7 and 8) and, less frequently, the apophyseal portion (figs. 9 and 10).

This bone tumor causes resorption of the epiphysis (or apophysis), erosion of the bone cortex and joint invasion, leading to arthralgia, which can cause deformity and joint subsidence fracture.

The treatment of both osteoblastoma and chondroblastoma is surgical and must be carried out as soon as possible, as these lesions, despite being histologically benign, quickly progress to destruction of the local bone framework.

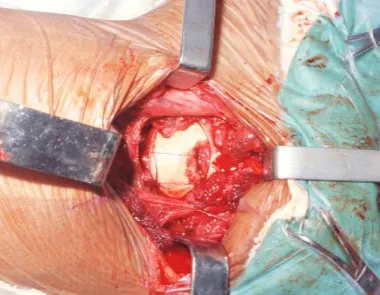

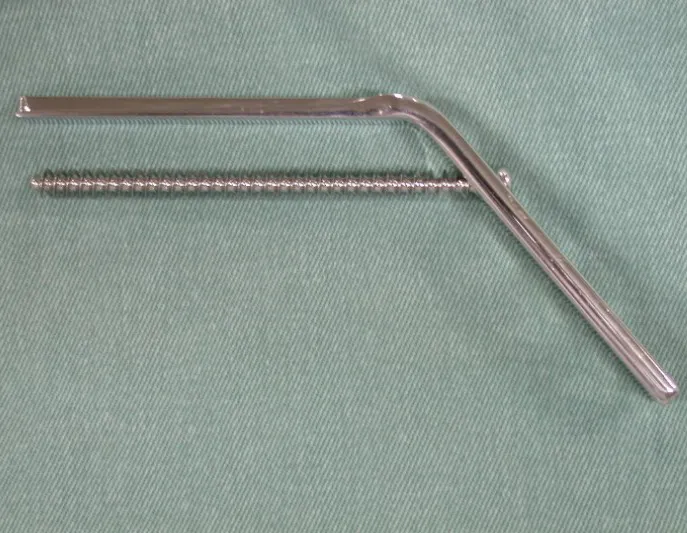

The best indication to avoid local recurrence is segmental resection. However, due to the articular location of the chondroblastoma, it is preferable to provide adequate surgical access to each region, as in this example that affects the posteromedial region of the femoral head (fig. 11), to perform careful intra-lesional curettage, followed by local adjuvant , such as phenol, liquid nitrogen or electrothermia (fig. 12), to subsequently fill the cavity with an autologous bone graft, restoring the anatomy of the region (fig. 13) and reestablishing function (figs 14 and 15).

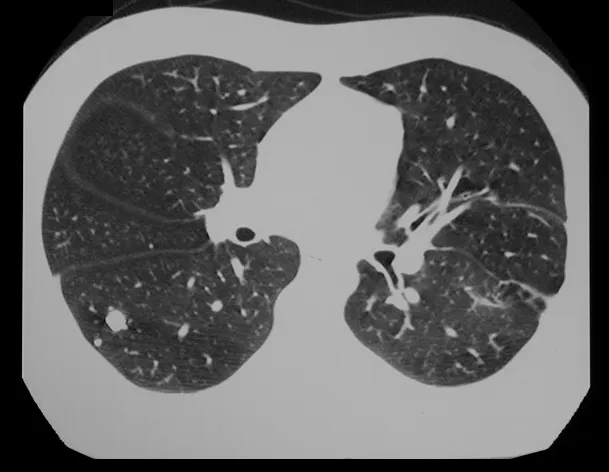

In our experience we had two cases of osteoblastoma and one case of chondroblastoma with secondary lung disease. In this case of chondroblastoma, thoracotomy was performed and numerous pulmonary nodules were found, which persist to this day. This patient, at the time of diagnosis of metastases, presented with hypertrophic pulmonary osteopathy. He did not undergo any complementary treatment and is asymptomatic to this day, thirteen years later (fig. 18 and ’19) and fifteen years after surgery (fig. 20 and 21).

Malignant Bone Tumors:

The most common malignant bone neoplasms in childhood are osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma, which must be diagnosed at the onset of symptoms, as they cause pain and a palpable tumor and need to be treated early.

Osteosarcoma –

In our country, it is not uncommon for osteosarcoma to present with a fracture at diagnosis (figs. 22 and 23).

Ewing sarcoma –

Ewing’s Sarcoma is a malignant bone tumor that can be confused with osteomyelitis and can be diagnosed after a fracture (figs 30 to 36).

Click here to see the full case

In children, cases of malignant neoplasms that lead to fractures are fortunately rare.

Pseudotumorous Bone Lesions:

The bone lesions that most frequently accompany fractures in children are pseudo-tumor lesions, with emphasis on simple bone cysts, aneurysmal bone cysts, fibrous dysplasia and eosinophilic granulomas, in this order of frequency.

Eosinophilic granuloma –

Eosinophilic granuloma presents as a local inflammatory condition and a lesion with bone rarefaction accompanied by a thick lamellar periosteal reaction, which is a radiographic characteristic of benignity. Another aspect of eosinophilic granuloma is that it presents an area of bone rarefaction without corresponding extra-osseous involvement (fig. 37), distinguishing it from Ewing’s sarcoma, which is the tumor that presents the earliest extra-cortical tumor.

Eosinophilic granuloma can present with a clinical picture of fracture when it affects the spinal column where a wedging fracture of the vertebral body occurs, described as Calvé’s vertebra plano (fig. 38). In this situation, this injury may progress to spontaneous healing, and restoration of the vertebra body may even occur.

Other locations where micro-fractures can occur are when they affect the supra-acetabular region (fig. 39), or in load-bearing areas such as the proximal metaphyseal portion of the femur (fig. 40), due to cortical erosion. medial.

This lesion responds well to simple curettage surgical treatment, with the need to add a bone graft being exceptional.

Fibrous Dysplasia –

Fibrous dysplasia is a pseudo-tumor lesion that most frequently leads to bone deformity. However, when it affects the femur, it can cause a previous deformity, like a shepherd’s crook, characteristic of this condition, with consequent fracture (fig. 41). The femoral neck region with fibrous dysplasia often develops a fracture, even without previous deformity (fig. 42).

To correct the defect, it is necessary to curettage the lesion, fill it with autologous bone graft and corrective osteotomies of the deformity (fig. 43). A fracture in this location can be difficult to resolve, due to the difficulty in consolidation due to the dysplastic appearance of the bone (fig. 44), leading to recurrence of the disease and deformity.

Fibrous dysplasia may also be part of congenital pseudoarthrosis, which most frequently affects the distal third of the tibia, but can occur in other locations such as the proximal third of the tibia (figures 52, 53 and 54), with all the difficulties in reaching it. if consolidation.

Congenital pseudoarthrosis is a condition that deserves to be studied in a separate chapter.

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst –

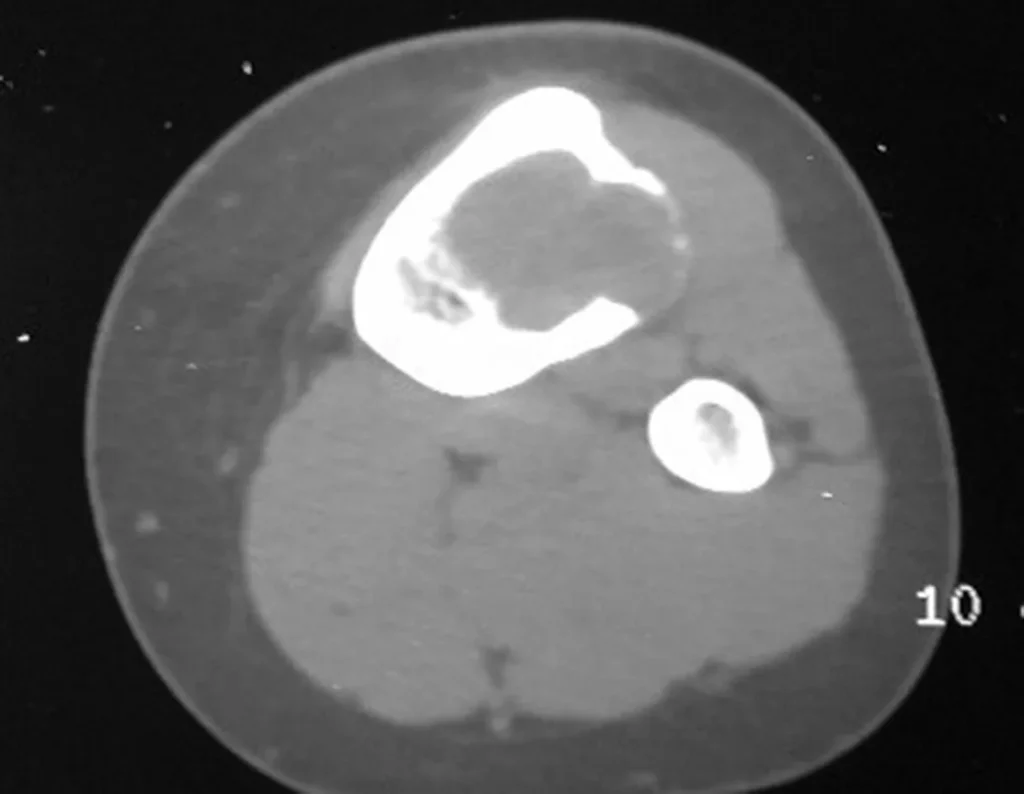

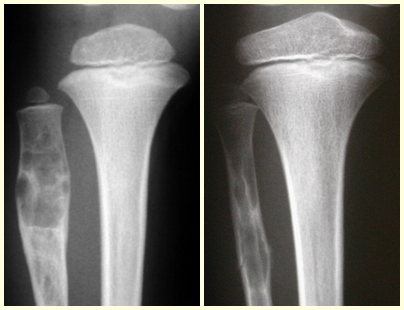

The aneurysmal bone cyst, also called multilocular hematic cyst, is a lesion of insufflative bone rarefaction filled with serosanguineous fluid, interspersed with spaces varying in size and separated by septa of connective tissue containing trabeculae of bone or osteoid tissue and ostoclastic giant cells ( figs. 55 and 56).

The patient generally presents with mild pain at the site of the injury, when the affected bone is superficial, and inflammatory signs such as increased volume and heat may be observed. Generally, the patient correlates the onset of symptoms with some trauma.

In evolution there may be a slow, progressive or rapidly expansive increase. It affects any bone, most frequently the lower limbs, tibia (figs. 57 and 58) and femur representing 35% of cases.

The vertebrae are also affected by this injury, including the sacrum. In the pelvis, the iliopubic branch is most frequently affected. They can mimic joint symptoms when they reach the epiphysis. Compromise in the spine can cause compressive neurological symptoms, although in most cases it affects the posterior structures.

The treatment of choice has been marginal resection or intra-lesional curettage, followed by filling the cavity with an autologous or homologous graft, when necessary. The cavity can also be filled with methylmethacrylate, although our preference is to use an autologous graft when possible, as it is a benign lesion. Some authors associate intralesional adjuvant treatment with the application of phenol, electrothermia or cryotherapy. In classic aneurysmal bone cysts, I do not see the point of this therapy, which, however, should be applied when the surgeon finds a “suspicious” area that was not detected on imaging. If the aforementioned benign tumors are involved, which may be accompanied by areas of aneurysmal bone cyst, local adjuvant therapy will be beneficial.

Some bone segments such as the ends of the fibula, clavicle, rib, distal third of the ulna, proximal radius, etc. can be resected, without the need for reconstruction.

In other situations, we may need segmental reconstructions with free or even vascularized bone grafts or joint reconstructions with prostheses in advanced cases with major joint involvement. In the spine, after resection of the lesion, arthrodesis may be necessary to avoid instability.

Radiotherapy should be avoided due to the risk of malignancy, however it may be indicated for the evolutionary control of lesions in difficult to access locations, such as the cervical spine, for example, or other situations in which surgical re-intervention is not recommended.

Embolization as an isolated therapy is controversial. However, it can be used preoperatively to minimize bleeding during surgery. This practice is most used in cases of difficult access, although its effectiveness is not always achieved. Infiltration with calcitonin has been reported with satisfactory results in isolated cases.

Recurrence may occur, as the phenomenon that caused the cyst is unknown and we cannot guarantee that surgery repaired it. The recurrence rate can reach thirty percent of cases.

Simple Bone Cyst –

A simple bone cyst is a pseudo-tumor lesion that can occur in any part of the skeleton and most frequently presents with fracture (figures 59 to 64).

A simple bone cyst can occasionally be diagnosed due to an increase in volume, but when it presents a painful symptom, it is generally related to micro fractures or often a complete fracture.

The humerus is the most affected bone. Micro-fractures can eventually provide partial “cure” in some areas of the cyst and with growth the metaphysis moves away from the lesion, which begins to occupy the diaphyseal zone (fig. 65 and 66). This progression to the diaphysis can occur asymptomatically and a new painful clinical manifestation may occur acutely (fig. 67).

In these situations, the treatment adopted must be appropriate for the bone and the fracture in question, and may be closed or open, with the indication of filling with a bone graft depending only on the specific needs of the fracture, when surgical treatment is indicated.

In mature bone cysts, the complete fracture causes great decompression of the lesion and consolidation and healing of the lesion can be achieved simultaneously. However, in some cases, there is a need for additional treatment of the cyst, after consolidation of the fracture, when closed treatment is chosen (fig. 72 to 78).

Click here to see the full case

Stress Fracture –

Stress fractures deserve special attention in this article both because they are more frequent than reported in the literature, as many cases go unnoticed, and because of the florid appearance that imaging studies portray, causing difficulty in differential diagnosis.

The child complains of pain, usually after physical exertion, which, as it is mild, ends up resolving spontaneously.

However, an orthopedist may be consulted and, when requesting an x-ray, be surprised by a periosteal reaction in the metaphyseal region in a growing patient.

The concern about the possibility of osteomyelitis, eosinophilic granuloma, osteosarcoma or Ewing’s sarcoma is justified, but it is necessary to be aware of clinical aspects, such as time of evolution, improvement factors, local appearance, so as not to complicate this diagnosis, which is clinical. radiological (fig. 96 and 97).

It is necessary to evaluate and ask: in the time it took to carry out these tests, was there no clinical improvement?

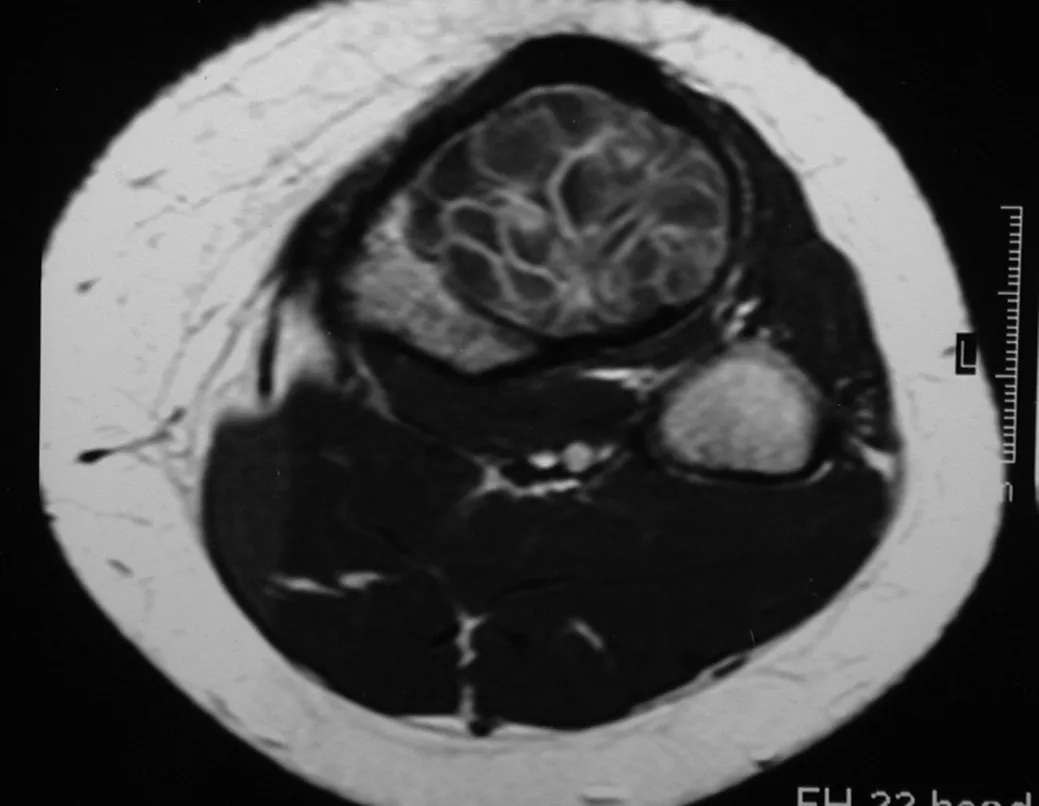

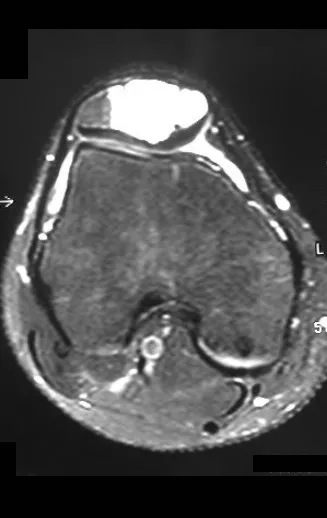

Magnetic resonance imaging is an exam that needs to be interpreted very carefully, as the fracture causes intra- and extra-osseous edema that can scare less experienced people.

We must observe the detail of the two low signal points of the fracture callus in the lateral and medial cortex in figure 100 as well as the low signal point of the bone callus in the posterior cortex in figure 101.

The inflammatory process of the fracture, with marked hemorrhage and edema, is extensive. The histology of the fracture callus may mimic osteosarcoma. There is a known case of amputation due to an erroneous diagnosis of osteosarcoma in a patient with a stress fracture.

Observation for two to three weeks is essential for an accurate diagnosis and is not considered bad practice, even in neoplasms. The x-ray taken three weeks later showed the stress fracture (fig. 102 and 103) and the clinical picture with improvement in symptoms and reduction in edema reaffirms the diagnosis. The clinic is sovereign.

Author: Prof. Dr. Pedro Péricles Ribeiro Baptista

Orthopedic Oncosurgery at the Dr. Arnaldo Vieira de Carvalho Cancer Institute

Office : Rua General Jardim, 846 – Cj 41 – Cep: 01223-010 Higienópolis São Paulo – SP

Phone: +55 11 3231-4638 Cell:+55 11 99863-5577 Email: drpprb@gmail.com